The primitive history

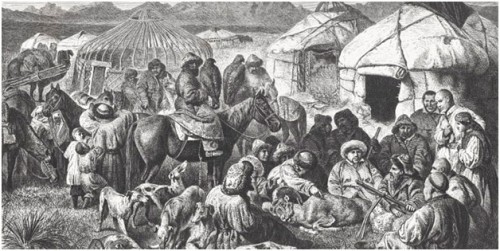

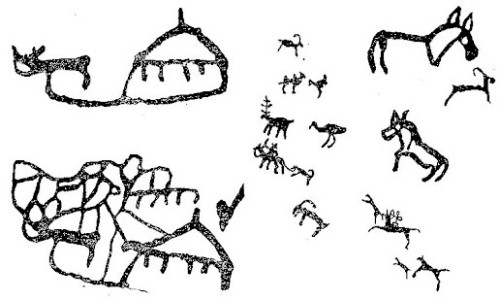

The earliest evidence of human settlement in the territory of modern Kyrgyzstan, discovered in the Central Tien Shan (near Lake Issyk-Kul) and in the Fergana Valley, dates back to the Paleolithic era. Additionally, artifacts from the ancient Stone Age were found in the southern Kapchigay region. Subsequently, about 5-10 thousand years ago, evidence of Mesolithic hunters emerged (Middle Stone Age) along the shores of Issyk-Kul. These hunters decorated the walls of the Ak-Chunkur cave with red ochre, portraying the scenes of hunting and dance. Indigenous tribes inhabiting this Central Asian region engaged in the crafting of stone tools and ceramics, while also utilizing bows and arrows for hunting. Later, in the Bronze Age, people increasingly began to use tools made of bronze, and later copper. Isolated communities of farmers and herders lived in various regions of Kyrgyzstan.

Antiquity

In ancient times, the western lands of contemporary Kyrgyzstan constituted a segment of the ancient region of Sogdiana, inhabited by settled Iranian tribes with ties to present-day Tajiks. These tribes were affiliated with the Pamir-Fergana ethnic group, considered the easternmost subdivision of the Europoid race, whose descendants predominantly reside in Central Asia, particularly among Tajiks and Uzbeks. Their religious beliefs centered around the worship of fire, following the tenets of Zoroastrianism.

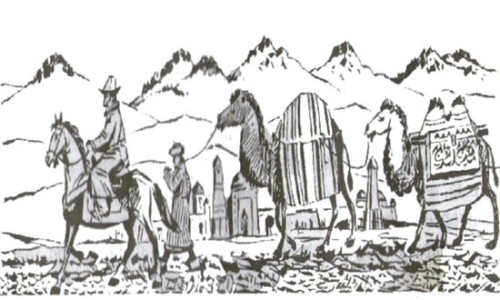

In the northern expanse of the region, nomadic Saka tribes traversed the land. This confederation of tribes endured from the 7th to the 3rd century BC. Subsequently, during the 2nd century BC, certain Massagetae and Saka factions allied with the Usun tribe, forming a tribal coalition that persisted until the 5th century AD. By the 2nd century BC, the southern territories were incorporated into the Parkan realm, while from the 1st to the 4th centuries AD, they fell under the dominion of the Kushan Kingdom. During the early medieval period, Turkic incursions penetrated the lands of Kyrgyzstan. By the 7th century, Kyrgyzstan's territory had become integrated into the Western Turkic Khaganate. By the beginning of the 8th century, political authority vested within the Turkic confederation, a coalition of Turkic tribes. However, by the mid-century, these territories fell under the control of the Karluk tribal alliance. During this period, there was a proliferation of cities and settlements in the valleys of the Chu and Talas rivers. Farmers engaged in vigorous commerce, trading not only with nomadic tribes but also with extensive caravans traversing the Chu River valley along the Great Silk Road, connecting Eastern Europe to Southeast Asia. It was during this juncture that the Kyrgyz ethnicity made its inaugural appearance in the region.

Kyrgyzstan played a vital role along the Great Silk Road. The city of Osh, situated in the southern part of contemporary Kyrgyzstan, has been a crucial transit point on the Fergana branch of the Great Silk Road for centuries due to its favorable geographical positioning. Indigenous inhabitants provided services to travelers and caravan merchants. Osh, renowned as a favorable trading post and exchange center, drew in merchants, artisans, herders and farmers.

The Kyrgyz

The Kyrgyz people first appear in historical records within the Chinese chronicle "Shi ji," authored by the Chinese historian Sima Qian. Within this chronicle, ру recounts the military campaign led by the Xiongnu chieftain Shan yu Modu, also known as Modu. The Kyrgyz ru referenced in this account under the designation of "gegun." There remains ongoing debate regarding the precise habitation of the Gegun people. Some sources suggest they were nomadic within the expanse of the Great Lakes Depression in western Mongolia. Alternatively, ancestral Kyrgyz presence is speculated to have been situated north of the Borohoro Mountains (Eastern Tien Shan) and west of the Dzungarian Alatau desert in Dzungaria, located in western modern China.

Incorporation into Tsarist Russia.

The process of incorporating Kyrgyz lands into Russia commenced in the mid-1850s. In defiance of the oppressive rule of the Kokand khans and driven by a desire to liberate themselves from this subjugation, the Kyrgyz tribes, like many others, willingly embraced Russian citizenship, viewing it as a means to gain independence from Kokand. Consequently, between 1855 and 1863, expeditions led by Tsarist Colonel Chernyaev claimed territory in Northern Kyrgyzstan from the Kokand Khanate, subsequently integrating it into the Russian Empire. The establishment of the Przheval'sk outpost marked the beginning of Russian presence on Kyrgyz soil.

Southern Kyrgyzstan (including Fergana and the northern part of Tajikistan) became part of the Russian Empire as the Semirechye region (with the administrative center in the city of Verny) following the defeat of the Kokand Khanate in 1876.

The Russian government sought to refrain from intervening in the affairs of the Kyrgyz and other subdued Central Asian peoples until the onset of the First World War.

The Soviet Era

Following the 1917 revolution, two political entities in Kyrgyzstan joined forces: the "Shuroi Islomiya" group ("Islamic Council") and the nationalist party "Alash Orda," both striving for the nation's attainment of sovereignty.

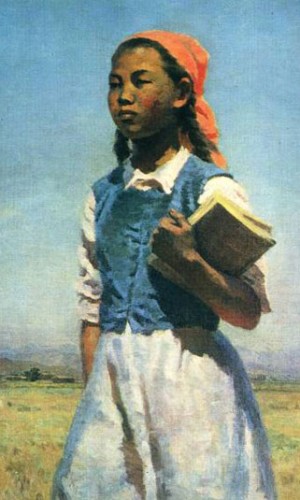

Upon Kyrgyzstan's integration into the unified Soviet state, the lifestyle of the Eastern Muslim nation and its inhabitants underwent profound transformations. In 1917, the principle of gender equality was proclaimed, and in 1921, legislation was enacted to prohibit polygamy and bride-price payments (kalym). In 1924, Kyrgyzstan was established as a distinct Kara-Kyrgyz Autonomous Region. In May 1925, the region was renamed as the Kyrgyz Autonomous Region, and in February 1926, it attained the status of the Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic (Kyrgyz SSR).

Due to Stalinist purges, reaching their peak between 1936 and 1938, the intellectual and creative elite of Kyrgyzstan, along with Muslim clerics, suffered near-complete annihilation. Additionally, Arabic-language books and manuscripts were targeted for destruction.

The democratic movement in Kyrgyzstan commenced in 1990. In October of that year, the democratic coalition successfully orchestrated elections, resulting in the election of the republic's inaugural president. Academician Askar Akayev was nominated for the position of the first president. On August 31, 1991, merely two weeks following the Moscow coup, the government declared the independence of the Kyrgyz Republic.

Present times

In the aftermath of gaining independence, the Kyrgyz Republic adopted its inaugural Constitution on May 5, 1993, which remained in force until the spring of 2010.

On March 24, 2005, Kyrgyzstan experienced the Tulip Revolution, leading to the ousting of Askar Akayev, who had governed the nation for fifteen years. He was succeeded by Kurmanbek Bakiyev. However, Bakiyev's presidency was short-lived. Just five years following the Tulip Revolution, he too was overthrown during another upheaval that rocked Kyrgyzstan on April 7, 2010.

2010-2020

During the years 2010–2020, following widespread public protests and the removal of K. Bakiyev from power, the Constitution of the Kyrgyz Republic underwent further revisions, leading to a significant enhancement of the roles of political parties and the parliament. Throughout this period, the country witnessed three different presidents: R. Otunbayeva (2010–2011), A. Atambayev (2011–2017), and S. Jeenbekov (2017–2020).

Despite maintaining a hybrid form of governance, the official and to some extent practical course of development underwent notable changes.

From 2020 onwards

After an extended period of the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting restrictions (2019-2020), along with irregularities observed during the parliamentary elections in the autumn, social unrest erupted in October 2020, culminating in widespread public protests and an unplanned change in government.

Upon assuming power, S. Japarov announced another round of constitutional reforms, signaling a shift towards a new form of governance – a presidential republic. This transition introduced a new political landscape characterized by an increased concentration of authority in the hands of the president, a reduced role for parliament in government formation, and a diminished influence over the overall political agenda in the country.